Dave Hofer of DuPage County Hardcore

Dave Hofer has lived a few lives. A suburban punk turned product buyer at Chicago’s esteemed Reckless Records, he spent a brief stint as a music journalist and currently works as an archivist at the city’s Art Institute. In his spare time Hofer runs DuPage County Hardcore, a Bandcamp-hosted trove of over 1,000 releases from Chicago’s rock and roll underground. The archive initially began as a chronicling of bands from Hofer’s adolescence–ones he played in, ones he played with–complete with a tongue-in-cheek title riffing on more famous regional scenes such as New York Hardcore. However, it quickly expanded outward, opening up to greater Chicagoland, before settling into a bound area: south of Wisconsin, west of Iowa, east of Indiana, and north of Peoria, Illinois (so chosen as a border due to its own well-documented punk scene).

As late capitalism lays waste to both the music and media industries, access to the music and history of the subcultures of the past is increasingly difficult. This casts DuPage County Hardcore as something of an anomaly, a wellspring of rare knowledge with no barrier to entry beyond a listener’s curiosity. Hofer is rigorously committed to the archive being accessible at zero cost (although he certainly isn’t against the odd appreciative donation). At one point DuPage County Hardcore had maxed out Bandcamp’s allotted free-downloads and, due to a quirk of their backend code, there wasn’t a way to restore that option to the whole page; Hofer manually added free downloads back to each of the hundreds of releases he had uploaded. As digital erosion continues to threaten the historical record, dedicated archival work like DuPage County Hardcore offers a hopeful model of how to preserve culture for future generations.

I spoke with Dave Hofer about the project’s origins, the physical processes behind media preservation, and how to consider archiving your own local scene.

Could you kick us off with a brief backstory of how you started the DuPage County Hardcore Project?

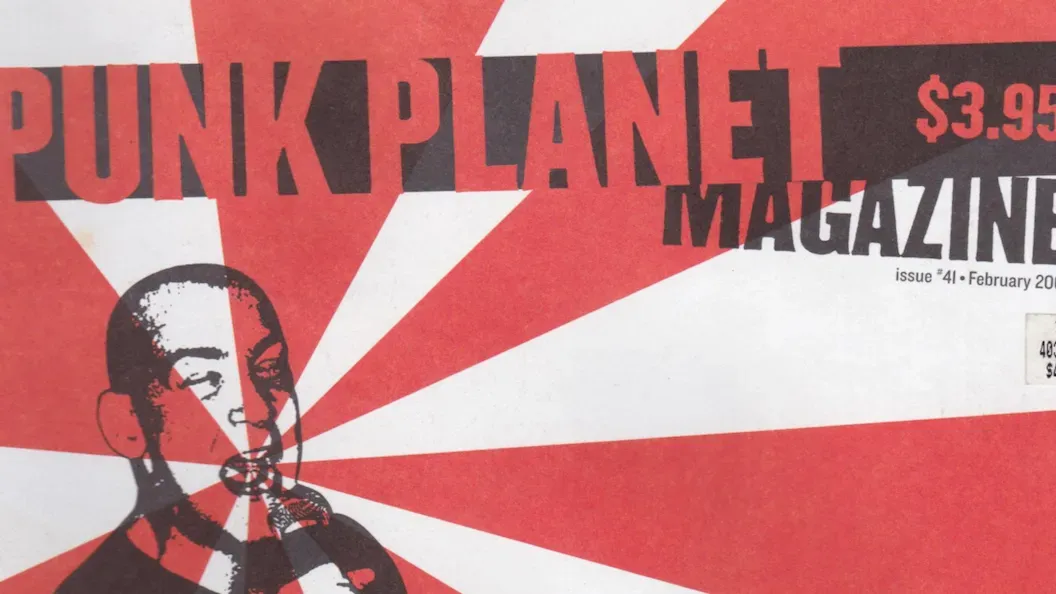

So circa 2003 to 2007, I worked for this magazine in Chicago called Punk Planet. I did a variety of Q&A interviews and caught the tail end of the freelance world, before everything really went online. I would record interviews with my old school landline into like a Radio Shack thing that would plug into the headset of the phone, and that would go into a cassette recorder–but you could get crystal clear recordings for transcribing. You know those tape racks that have space for a hundred cassettes in them? I had like two of those, and I knew I was never going to listen to those tapes again. I felt bad throwing them in the garbage, but I didn’t want to keep them. So I went to a good friend of mine who had the audio knowhow and he just gave me a crash course: download Audacity, this is the gear you need, here’s a very simple interface to get the stereo receiver or cassette deck to speak to your computer. And so I would just stick a tape in and just do the whole side as one track while I’m doing something else. [Mimes playing video games.] And then flip it over, do the other side. I would save the files and get rid of the tapes. I found some stuff from a band called Last in Line that my friend and I were in, maybe from ‘96 to ‘98, just a super fast hardcore band from the suburbs. And I thought I should digitize our old demo and get in touch with the other two guys. There was no digital version ever made. Initially I was just gonna put it on YouTube and send them a link. That’s when Bandcamp started kind of bubbling to the surface of mass usage. I decided to use that and it was basically off to the races.

Would you say that was when you started becoming interested in archival practices?

Yes and no. It really made me more aware of digitization efforts, turning analog into, hopefully, what’s going to be a format that’s usable for the foreseeable future. And the idea that tapes deteriorate–I hadn’t really considered that before. In passing I thought it would be sick to, say, digitize a seven-inch, but never really considered it from a practical point. I worked in a library during my undergrad, so it was always kind of in the periphery. Once I got into school and actually learned about the different processes of archival work, the handling of physical materials, the science behind it and everything, that’s when it really got driven home that for the last six years I’d been doing a variation of this without really thinking about it.

Is the physical process still mostly the same?

It’s definitely changed over time. Again, I’m a complete novice. I do a very basic signal evening on a lot of the cassettes I have. I’ve had people tell me apropos of nothing, “Man, the copy of the 7” that you uploaded sounds great!” And I’m just going off of my friend’s recommendation. I will clean up major pops and clicks, I get kind of nerdy in that way. In terms of getting as clean a rip as possible, it’s definitely evolved over time–you learn as you go. And the equipment has changed across the board. I’ve gotten a way better turntable since. A friend of mine gifted me a nicer interface than the one I’d been using, with more inputs. You can set the track levels to right under where it’s clipping, you can do each individual input on a left and right channel; You can really dial it in. And I started using a metadata editor, rather than just the built-in one with Audacity. Looking back, so many things were such a pain in the ass unnecessarily.

Do you ever think about trying to affiliate with a larger cultural institution?

No, it’s kind of touchy. Having been in the real deal environment now, you’re covering your ass at every turn. There are so many forms and deeds of gift, legal has to look at this and that. This is essentially a bootleg project. Not that I’m trying to make money, like a traditional bootleg, but I’m not getting everybody’s permission. But it’s interesting because there are other similar projects: there’s a Kansas City Hardcore archive on Bandcamp, that’s just off the top of my head. There’s maybe a Quad Cities, like Iowa, I’m pretty sure there’s one for that. And then I’m sure there’s other stuff, but I don’t know if people turn a blind eye or what the deal is. I’m always just kind of prepared for it to disappear tomorrow. Basically, since the dawn of blogs, there have been mp3s, and there’s a crazy precedent for this kind of free file sharing of underground music. I’m not the first person nor the last to do this kind of thing. With technology now, the laws are so far behind. It’s this weird gray area, where if you’re not being sinister or doing something sleazy, people seem like they’re fine with it. It’s sort of the whole idea of the punk thing. My friend once told me more people have heard his first band’s 7” than ever would have if they’d just put it out again normally.

It’s like Sophie’s Floorboard. It’s hard to imagine who would go and try to remove their music from a place where people are finding it who wouldn’t otherwise be able to.

Yeah, I mean that has happened a couple of times over the years but it’s super rare. But I get it. It’s been a variety of things. One guy was just super embarrassed because it was just some cringy 90s rock with dumb lyrics. He was a teacher. So I just took it down immediately. And other people for whatever reason just say, “I did not give you permission blah blah blah.” I always kill them with kindness: “No problem, I took it down already. Do you want the files for your own page? Do you want the scans?” Nobody ever replies to me. But over 11 years that’s happened maybe five times. Because I think people recognize the intent of what I’m trying to do.

So when you started the archive, Spotify was just starting to become the dominant way people consume music. Do you think the shift from mp3s to streaming has changed what you’re doing at all?

No, because you still have to seek it out. I like to think people are basically doing the iPod thing when they download music from the archive, whether they have everything on a hard drive that they stream in their living room or they do what I do where they keep a ton of shit on their phone. Just having a local music library. And when you download something, I always scan all the artwork. It’s basically giving people the opportunity to electronically have this 7”, or this cassette, like you don’t just have the tracks but you can also look at all the weird liner notes and everything. I don’t know how many people do that, but it’s just about preserving that. There’s a lot of history in there.

As legacy and modern music media continues to collapse–VICE scrubbing the website, Pitchfork getting folded under GQ–do you think this kind of archival work could supplant or replace what websites like that were doing to keep historical record?

Yeah, well there’s already the Internet Archive. For example, the magazine that I worked for, Punk Planet: It was 80 issues and sometime over lockdown somebody painstakingly uploaded it all. They must have taken out all the pages to get super flat scans and uploaded all 80 issues to the Internet Archive. It’s all optical character recognition, PDF scans. You can search all the contents, it’s fucking awesome. And like every issue of Maximum Rocknroll is up there. It’s 300 something issues. If Bandcamp disappears tomorrow, I have everything. I’ve talked with friends that are more tech savvy about how I could put this on its own site but still keep a kind of donation model in place. That’s not make or break, I could do it purely for free. But I will admit that with the time it takes… It doesn't hurt every now and again when somebody’s like, “I appreciate this, here’s five bucks.” But then you get caught up in the payment processing world where, again, this is sort of glorified bootlegging. It would probably just have to be a free model on the internet, or somehow use the Internet Archive. I’ve thought about that too, just to move everything there under its own collection, because that seems like it’s going to exist in perpetuity. I do see it as being at the mercy of Bandcamp, so it’s like, that could be the next VICE where it’s just scrubbed, or like MySpace.

And then they have that archive of MySpace music that’s massive, and they think it’s maybe only a third of whatever was up there.

Yeah it’s fucked. I always think of a band on my page called the Blue Meanies who are from here, were in their peak in the mid to late 90s, toured and everything. I thought this band would never be forgotten. Flash forward 20 years and I have more of their material on my pages than they do on theirs. Shit just gets lost to the sands of time. I’m not really looking at it like I’m doing a public service. I’m just doing this because I think this shit is awesome and should be remembered.

If this does become the model, there’s a huge opportunity cost for anybody who wants to do this kind of archiving. It’s basically a library, but it’s also time and effort out of somebody’s day with minimal compensation. How would you advise somebody on how to do this sustainably and not burn out?

I would say one, you just have to have that disposition, where you feel like you have an idea worth pursuing. I am going to pursue this until it is proven to be a waste of time. And that goes for anything, any band I joined–I would say yes to everybody because in the 90s all my friends were in three bands at once. You just do it until it’s not sustainable anymore for whatever reason. I guess it depends on how much material you’re working with too, because for this, the well seems like it’s unending. But you just have to have that disposition to see it through. If you know that your town had these four big bands, and they put out a finite amount of things, you can kind of gauge: Do I have the bandwidth to do this? How long will this take me? In my case I would also say people appreciating it, the positive feedback, is a key thing. The other prong of advice I would give would be to break up the workflow. Especially with things you have to digitize in real time: CDs, tapes, records. I’ll let that go, do something else, rip an entire side. Then another time I’ll sit down and break it up into tracks, and then another time I’ll take a little pile of stuff and sit there and scan while I watch TV. Then you just keep a folder for each release and keep building it until shit is ready to go. And I like to have a little backlog where I can post a bunch of shit, like five days in a row or whatever. The other thing is that I’m not beholden to anybody. I feel no pressure to create content, I just sort of do it when I can. But I enjoy it, so I make time for it.

Do you have any other general advice for someone interested in a similar undertaking?

I feel like the devil is in the details. In terms of scanning the artwork, I’ve never been super strict but I like to include as much as I can. I would say I prefer to have something available, rather than nothing at all. One thing that I really have learned working in the archival and library world is that you can’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. If all I have is an old JPEG that I had to upscale to meet Bandcamp’s minimum cover requirements, I’m not thinking I will only put a true scan up there–then so much shit wouldn’t be up there. Or how they only accept lossless audio formats, but sometimes people just have a 192 kBPS MP3, and so I just re-export it as a FLAC file and upload it. We may never get a better version of this. So fuck it, you know? And of course a tiny part of me is killed when I upload something and there’s a typo in a song title or a file name. I’ll catch it later and fix it. And man, it kills me that there are versions of this release out there now with a typo in the metadata. But you can’t control that stuff. Just try to get it right the first time and pay attention. But it’s also a hobby, so I can only care so much. It’s a balance.

Could you recommend some releases for people to check out after this?

Yeah, totally. I’ll start with a few from the same “family tree,” so to speak:

American Mosquito - Goddamn Cop - This was a studio project by Jeff Bachner and Jeff Jelen. Bachner was the original vocalist of MK-Ultra and before that, Weedeater. Jelen was the guitarist for MK-Ultra and Charles Bronson. When Bachner decided to play shows, he enlisted my sister Alison to play bass.

MK-Ultra - Melt - This is the band's second 7" and blew all of our minds when it was released. Very fast and brutal!

Weedeater - Get The Job Done - Late '80s / early '90s hardcore from the suburbs of Chicago. This is true DuPage County Hardcore! A local classic.

The Flim-Flams - The Flim-Flams - Keeping with the same family tree, this band consisted of three members of The Vindictives, my sister Alison, and Joey Vindictive's wife, Jenny. They recorded this awesome 6-song LP, as well as two other songs that never saw the light of day (and possibly never had vocals recorded), yet never played a single show. A real diamond in the rough.

And then here are a few more awesome ones:

Apocalypse Hoboken - Strikes Back - This is the first 7" I ever bought and happens to contain three of their best songs in my opinion. Legendary Chicago band; they never got enough props outside of Chicago. Speaking of . . .

Sludgeworth - Sludgeworth - Another band that just never quite made it outside of the area, this band features two ex-members of Screeching Weasel and the artwork on this 7" is by James O'Barr, who created The Crow. Uber-catchy power pop like only the Midwest can do!

The Mushuganas - Dropout Girl - The Mushuganas were one of the best bands from this area during their existence. They evolved from snotty pop-punk into more straightforward garage rock 'n' roll over time, but this is their finest hour.

Psychedelic Khrushchev - Wimpy Indie Rock Crap - Our hyper-local DuPage scene reflected the greater scene's variety in releases like this cassette, which is more Sebadoh than Minor Threat.

Under the Silver Linden - Under the Silver Linden - A digital-only, one-man project released by HeWhoCorrupts (the label), by HeWhoCorrupts guitarist Zack Petrusa AKA Caz UL Friday. Precise, creative grindcore. Absolutely incredible material!

This interview was lightly edited for length and clarity.